Well, that was unexpected...

How Matthew and Luke Portray the Temptation of Jesus Pt. 2

In the previous post, we surveyed some basic ancient Greek grammar to provide a foundation for how New Testament authors portray or tell the story of the temptation of Christ. We now look at Matthew (one of Jesus’ earliest followers) and this strange thing called the “Historical Present.”

Matthew’s use of the Historical Present

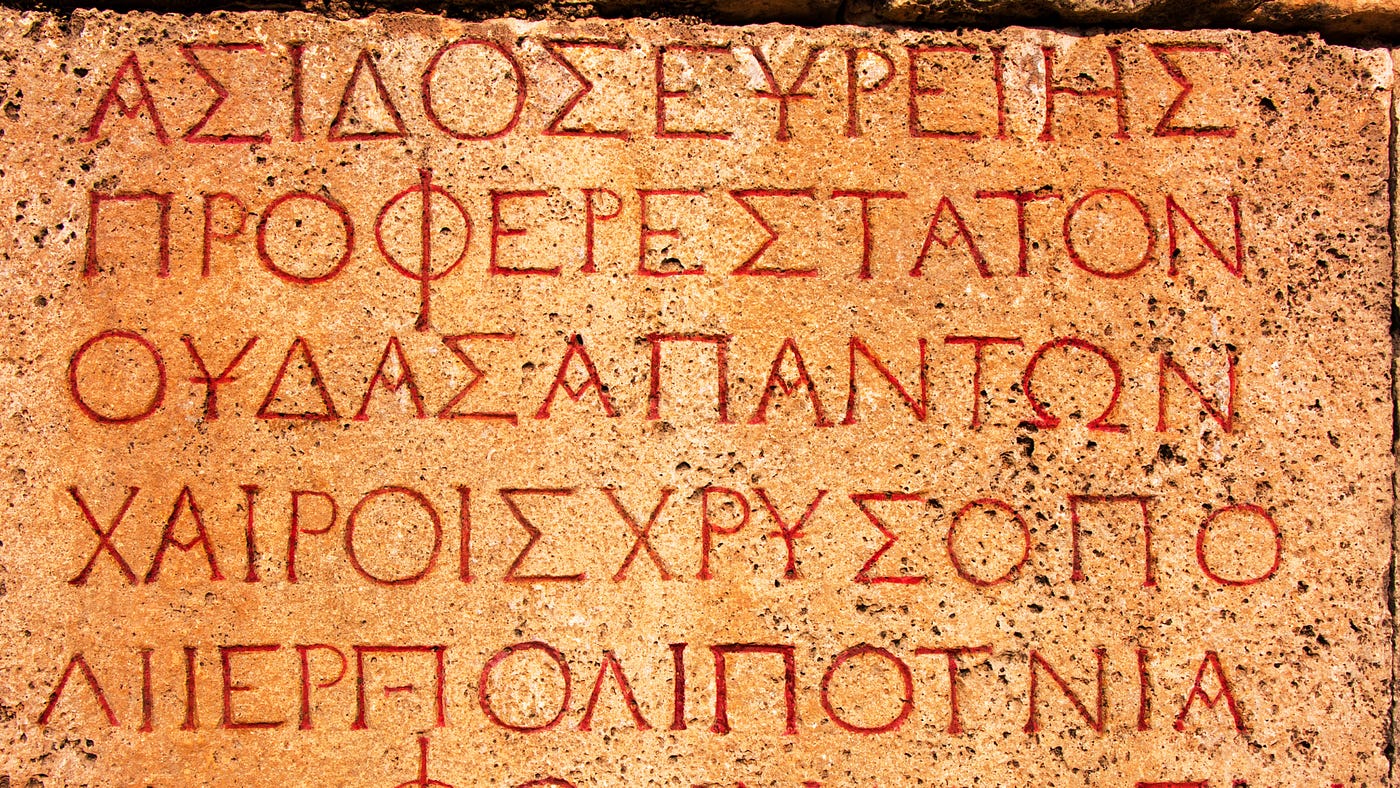

The pericope begins with Matthew introducing a new scene. He writes, Τότε ὁ Ἰησοῦς ἀνήχθη εἰς τὴν ἔρημον ὑπὸ τοῦ πνεύματος πειρασθῆναι ὑπὸ τοῦ διαβόλου “Then Jesus was led or brought up into the wilderness by the Spirit to be tempted by the devil” (This and the following translations are mine). The word Τότε is the adverb that functions to develop the narrative and modify the verb ἀνήχθη, effectively transitioning the reader from the scene of Christ’s baptism. In classic narrative fashion, Matthew employs the aorist tense throughout the first 4 verses, giving the reader a very fast-paced approach to the narrative. But then a shift takes place in verse 5.

He begins with the verb παραλαμβάνει, which is the present tense form of the verb παραλαμβάνω, meaning “to take along.” Satan here is taking Jesus with him to tempt him with his second temptation, and the fact that παραλαμβάνω is in the present tense ought not be surprising; it’s not uncommon for verbs of motion to be in the present tense in narrative passages. This is what is typically known as the “Narrative Present” or “Historical Present” (HP hereafter).

Every language makes use of an HP one way or another. Steven Runge defines the HP this way: “It is a present verb, normally associated with present time, being used in a past-tense context.” Elizabeth Robar further describes the HP as the tense “that is used instead of a past tense, when that past tense would not only have been perfectly acceptable, but the semantics of the past tense are still understood to obtain despite the present tense form in the text.”

There is a range of options presented to the authors of Scripture when developing a narrative. In narrative texts, something that the authors desire to establish is “prominence”–the guidance given to the reader to help them understand what is most important or where attention ought to be drawn. Stephen H. Levinsohn, in his article on grounding in narrative, points out that the aorist tense is the default way to establish natural prominence and express the past tense in narrative. One other way is the HP. But since the HP “is not the default way of portraying an event in narrative…” it must have “added implicatures.” In sum, the HP is a mismatch of both tense and aspect. Normally, the aspect of the present tense is of an ongoing, progressive nature, but the aspectual value of the HP is normally reduced to zero. Therefore, while these are necessary to take into account, tense and aspect are not the main focus when evaluating the narrative with the HP.

Building upon the general principle that choice implies meaning, Steven Runge helpfully points out that “the use of the present form in a past-tense setting represents the choice to break with expected usage.” So, when looking at the narrative in Matthew’s gospel once again, in each of these five HPs, the reader must discern Matthew’s purpose in breaking away from the norm. Circling back to verse 5, Matthew writes, “Τότε παραλαμβάνει αὐτὸν ὁ διάβολος εἰς τὴν ἁγίαν πόλιν καὶ ἔστησεν αὐτὸν ἐπὶ τὸ πτερύγιον τοῦ ἱεροῦ.” Right before this, Matthew employs the aorist tense verb ἀνήχθη to describe the Spirit’s action in leading Jesus into the wilderness. And now he transitions to παραλαμβάνει. Two helpful questions to ask are: What is the motivation for its use? And what is the scope of its effect?

By employing παραλαμβάνει, Matthew seems to be using a two-pronged approach: a processing function–simply providing discourse boundaries and marking off new paragraphs, and a discourse-pragmatic function. “It has a cataphoric function; that is, it points on beyond itself into the narrative, it draws attention to what is following.” In other words, the motivation here is to provide highlighting and establish prominence. It serves as a forward-pointing device so that the reader’s attention will be drawn, not to the verb itself, but to the following speech or event. Although each temptation the devil gives calls upon Jesus to perform something extravagant and miraculous, the pattern seems to be repeated with the more surprising and suspenseful parts of the narrative, which begins with verse 5.

Seven Weeks Coffee is a coffee company dedicated to supporting the pro-life movement, with over 5,000 unborn lives saved. This coffee makes for a perfect Christmas gift—type the discount code REFORMANDA to save on your first purchase!

Jesus and the devil are on the pinnacle or high point of the temple overlooking the beauty of the holy city (such is the kind of suspense with which the HP forces a reader to view this scene). Verse 6 continues, καὶ λέγει αὐτῷ· εἰ υἱὸς εἶ τοῦ θεοῦ, βάλε σεαυτὸν (and said to him, “If you are the son of God, throw yourself down…”). The use of the HP λέγει here serves to slow down the pace of the narrative and establish prominence in the development of the devil’s temptations–his command to essentially commit suicide, followed by his misuse of the Scriptures to ground his command. Will Jesus do it? Will he give in and throw himself down? Jesus, of course, said (“said” being ἔφη– interestingly, he departs from the HP, most likely to showcase the progression of Jesus’ victory over satan and his many tactics), quoting Scripture, “You shall not put the Lord your God to the test.”

In verse 8 there is a repetition of an HP, “Πάλιν παραλαμβάνει αὐτὸν ὁ διάβολος εἰς ὄρος ὑψηλὸν λίαν καὶ δείκνυσιν αὐτῷ πάσας τὰς βασιλείας τοῦ κόσμου καὶ τὴν δόξαν αὐτῶν καὶ εἶπεν αὐτῷ· ταῦτά σοι πάντα δώσω, ἐὰν πεσὼν προσκυνήσῃς μοι.” By using the same verb as verse 5, it seems to be pointing to a change of location and a very extraordinary temptation, causing the reader to slow down. The processing function simply establishes a new paragraph but also points to this temptation as not only the final one but the climactic part of the narrative. This verb points away from itself to the climax of the story, which alerts the reader to another suspenseful moment. Will Jesus give in and offer worship to the devil in exchange for the kingdoms of the world? Of course, he doesn’t, and Matthew once again employs an HP in verse 10, “τότε λέγει αὐτῷ ὁ Ἰησοῦς· ὕπαγε, σατανᾶ…” This emphasizes the victory of Jesus over the devil by relying upon the power of the Spirit and the authority of the Word of God. The final HP is in verse 11– “ἀφίησιν”– which is pointing to the change in characters. The devil was once with him and tempting him; now the angels are with him and ministering to him.

The scope of the effect of HP is the thematic features throughout the passage. It seems that by emphasizing the surprising events of Jesus’ refusal to throw himself down off the temple to make a big spectacle (drawing attention to his kingly power), his refusal to bow to worship Satan in exchange for the kingdoms of the world, followed by the angels ministering to him, Matthew is drawing the readers attention to the unexpected nature of Christ’s kingship and the fact that Jesus accomplished what Israel couldn’t.

Although Elizabeth Robar concedes, after reading a gospel scholar, that her hypothesis was wrong about the theme in Matthew of Jesus as the new Israel in this passage, there is a lot of merit to that view. It has the potential to arise from Matthew’s use of the HP. Even Robar concludes her essay and writes, “At least in Matthew, the HP is an editorial device to indicate thematic prominence: an aid to the reader or listener to discern the hierarchy of themes present, and in particular to know which themes are of intrinsic interest to the author himself.”

Conclusion

By establishing prominence in the places he does, Matthew demonstrates the surprising reality that, after passing through waters as Israel did (His baptism), he didn’t give in to Satan’s temptations in the wilderness as Israel did. He worshiped His Father alone, not establishing his kingdom using a public spectacle, but (ironically) through choosing the calvary road, wearing a crown of thorns to once and for all defeat Satan and triumph over all demonic powers (Colossians 2:15).

Unlike Matthew, Luke goes the traditional route with the same narrative in Luke chapter 4. This will be the subject of the next post.

Brother, that was a deep and beautifully written study. What struck me most is how the writer shows that even in the wilderness, Jesus wasn’t just resisting temptation He was revealing the heart of His Kingdom. While Satan tried to pull Him toward shortcuts, spectacle, and self-exaltation, Jesus chose obedience, patience, and the long road of suffering love. And honestly, that’s the road that leads to real victory. Hebrews 4:15 reminds us that Jesus was tempted in every way as we are, yet without sin, and that gives us courage when we face our own wilderness seasons. Matthew’s use of the historical present just pulls us right into the scene, making us slow down to see how intentional Jesus was with every answer He gave. He didn’t fight Satan with emotion but with Scripture, just like Psalm 119:11 says I have hidden your word in my heart, that I might not sin against You. And the beautiful thing? After every temptation, Jesus stands firm, showing us that the way of God is not through shortcuts but through surrender. Philippians 2:8 says He humbled Himself and became obedient unto death, even death on a cross and that’s the very obedience that rests beneath this story. Reading this reminds me that Christ didn’t come to impress the world He came to redeem it. He didn’t take the kingdoms of the world from Satan He won them through the cross. And brother, if Jesus overcame through Scripture, obedience, and the Spirit’s leading, then we can trust Him to strengthen us in our daily battles too. May the Lord help us walk in the same faithfulness, step by step, just as our Savior did.